Culinary Journeys:

Laurence Louie

Culinary Journeys focuses on chefs who have moved to the UK, in order to display how migration continues to shape the country’s gastronomic landscape, and thus highlight the importance of diversity within the hospitality sector.

We recently caught up with Laurence Louie, head-chef at Selin Kiazim’s East London eatery Oklava. The son of first and second-generation Chinese immigrants, Laurence grew up in Boston where he was introduced to cooking at an early age whilst working weekends at the family bakery.

After graduating from university, he spent 5-years working with non-profit and community organisations in Boston’s Chinatown, leading youth programmes and supporting the local migrant population with housing and employment rights.

However, it was during his subsequent trip to China (where he would spend almost a year) that he realised food was where his passion lay, and, upon his return to Boston, he took up employment at contemporary Eastern Mediterranean restaurant Oleana, before later, moving to London.

How would you describe your approach to food?

I’m still developing as a chef, but at its core, my practice is inspired by people, which I think comes from my previous social justice work.

Whenever I cook and create, I want it to be people-led: creating food that is from one person to another. I think that gets lost sometimes. A lot of people start with the quality of produce, which is great, but I want to stress through my journey, that as a chef you shouldn’t lose that human connection. I want to be able to create food memories, space, culture.

What has your experience been like working in the UK hospitality sector?

I worked in Boston at a couple of different places, and it is a much smaller food city, it is definitely a lot more intense here.

London is an important city on the world food map and has its way of creating more intensity and competition. There are just loads more restaurants and there is a buzz around them, which creates a faster pace. Food trends come and go, staff are mostly international and they also come and go. I couldn’t say how many people I’ve worked with in London, but the majority aren’t from the UK, especially in terms of the kitchen staff.

How do you think the hospitality sector has benefitted from migrant chefs?

I think there are two parts. First, immigrant labour is what makes most of these restaurants function, the backbones of the industry are founded on people that come from different places.

The narrative that people migrating from different places make the industry and it wouldn’t survive without them, is true. It is run on immigrant labour: the handwork that people put in, the KP’s, commis chefs, all of the dirty work that goes into it.

The other side is the creative aspect: contributions of culture, ingredients, ideas: chefs from international backgrounds come to the UK and contribute to a more vibrant and healthy, colourful restaurant landscape. A great chef would never close their doors to other cooking styles or cultures, that’s a key element of how food develops and grows within the industry. There is a line when it becomes cultural appropriation and issues around that, but perhaps that’s a separate conversation.

Immigrant labour and cultural creativity form the backbones of the industry.

How do you think your migration has affected your cooking practice?

For me, it’s about continuously learning. As a chef, you are inspired by the things around you, whether it be the food you are eating, ingredients, techniques, or things like that.

Growing up Chinese-American has been huge: the core of my home cooking has been Chinese food. Obviously, growing up in the US I’ve had hamburgers, pasta, meatloaf, but the most genuine and heartfelt cooking for me is Chinese.

However, Chinese-US food isn’t really considered its own category, but it is definitely distinct from food in China and even Chinese food in the UK. For example, in the UK there is a much bigger range and it’s not so limited. Growing up in Boston, there's either restaurants in Chinatown or the classic Chinese American takeaway spots.

At Oklava, we have an open policy for chefs to be able to contribute to menu items and specials. Selin ultimately has the final say, but for the day-to-day things as head chef, there is a lot of space for creativity. I’m always talking with Selin and other chefs in the restaurant about how we can make a dish more delicious.

Being a Turkish restaurant, there is a limitation to what we can do and there are a lot of techniques involved. But we always pull influences from other cultures. The way I roll dough is a Chinese technique, but that doesn’t mean it can’t work in a Turkish setting. The beauty of having a kitchen full of people from different places is that dishes naturally evolve through conversations you have with one another; it’s really beautiful. For me, the dream is to have my own Chinese restaurant. I never saw cooking Turkish cuisine as a hindrance to that. It’s all about cooking food.

Have you had to adapt your cooking as you have moved to different places?

Chinese food is everywhere around the world. A core piece of that is because it’s very versatile and has moved and evolved with the Chinese diaspora. Food is part of survival and has to be adaptable.

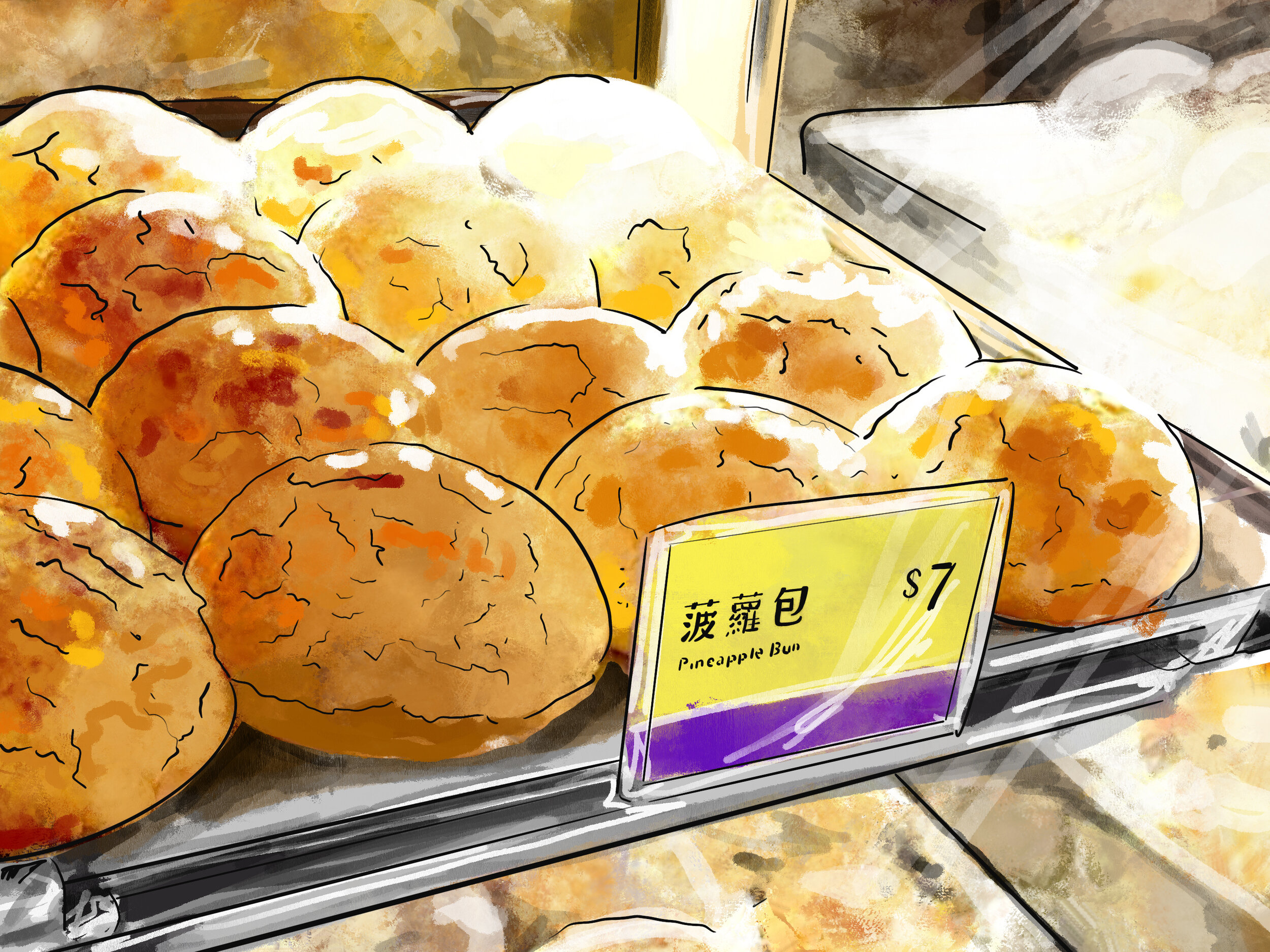

See Laurence’s recipe for Pineapple Bao. Here.

Illustrations © Diogo Rodrigues